Two Hundred Ten Down

I finished the second half of the bar exam Thursday evening. I was actually going to write a blog entry during the lunch break, perhaps to enter the book of world records as the only person ever to blog in the middle of a bar exam, but I decided it would be better to review Secured Transactions. As it turns out, there were no Secured Transactions questions on the essay portion, nor were there any Commercial Paper questions or several other areas of law I had studied intensely. It was a bit of a let-down, although I’m sure many people were happy not to see these questions.

I am firmly convinced that the material tested on the bar exam—particularly the multiple choice section—has almost no bearing on one’s ability to practice law. In fact, it might even prepare you to be a worse lawyer than you otherwise would be. Most legal questions are arguable, and if you’re in litigation it’s probably because the outcome isn’t clear. The most important skills you need to be a competent attorney involve dealing with clients, researching, writing, negotiating, developing creative arguments, etc.. Answering 200 multiple choice questions on doctrines that aren’t even the law any more in any jurisdiction (the Doctrine of Worthier Title, Shelley’s Rule, … even the Rule Against Perpetuities hardly exists anywhere unmodified) is pretty far off base.

Someday, when I have some stature in the legal community, I want to lead a charge to change this ridiculous examination once and for all. I admit that some sort of threshold exam is probably a good thing; and there might be some value to learning certain basic legal doctrine that you would not otherwise cover in law school (I certainly never learned anything about negotiable instruments).

A better exam, I think, would present you with a fact pattern that you couldn’t possibly have seen before that doesn’t fit neatly into any legal box, and ask you to analyze the situation and present possible theories for resolving the problem. Ideally, you wouldn’t even be able to classify the question as fitting into a particular doctrinal area, e.g., corporations vs. evidence. You would have to discuss how these all fit together: for example, there might be an issue of breach of fiduciary duty in a partnership but it might be difficult to ever prevail in court because of the hearsay rule and the statute of limitations.

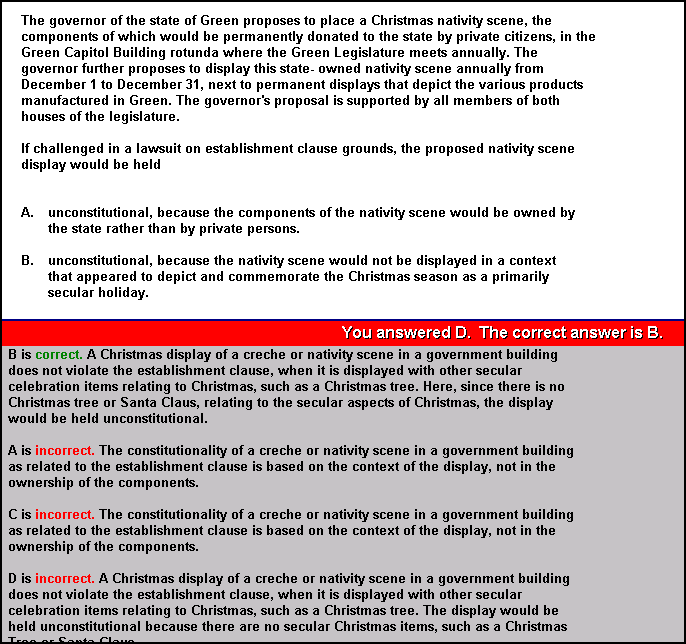

Instead, we get questions like this: