Filed under The Law by adam | May 19, 2005 | 0 comments

Noted IP practitioner and scholar William Patry started a blog. One thing I love about the blog so far is that he doesn’t write with the careful restraint of many active practitioners. He’s quite willing to talk about how badly courts bungled the law—which I suppose is justified, since he drafted some of the legislation at issue when he was the copyright counsel to the House of Representatives.

My favorite recent bit is from this commentary on the Bootleg Statute, which many—including some courts—have criticized as being unconstitutional under the Copyright Clause:

In 1994, I had been practicing copyright law for 13 years. I was well aware of the limited Times restriction. Everyone involved was aware of it. Do critics think that in making the bootleg right perpetual we meant to legislate under the Copyright Clause but just had a memory lapse, or that we said, “Hell, let’s draft an unconsitutional provision; why not, its bound to be fun?” The answer is, no, we didn’t draft a copyright or copyright-like provision at all. We drafted a sui generis right under the Commerce Clause. (For those who are wondering, Congress is not in the habit of saying in a statute, “hey this is the power we are legislating under.” See also Woods v. Taylor, 333 U.S. 138 (1948)).

Filed under The Law by adam | May 2, 2005 | 1 comment

Interesting evolving blog/article on The Future of Legal Blogging on Between Lawyers, a legal weblog I strongly recommend to lawyers and law students but for one problem: they only include a snippet of each blog entry in their RSS feed. In fact, all of the Corante-hosted weblogs seem to do this. I understand that they have commercial sponsors and would like you to visit the website so your eyeballs can be exposed to those sponsors’ names, but it seems like such a backwards way to do it. I usually read blogs offline through my aggregator (for example, on the train), and not being able to read the full entry means I often won’t see it at all.

slashdot seems to have recently solved this problem by including an occasional advertisement in the RSS feed itself. Why hasn’t anyone else figured this out?

Update: I stand corrected. Strangely, http://www.corante.com/betweenlawyers/index.xml gives the full text in the feed; http://www.corante.com/betweenlawyers/index.rdf does not. I was automatically subscribed to the .rdf version by my newsreader. I wonder if this is intentional.

Filed under The Law by adam | March 7, 2005 | 0 comments

Jack Balkin makes the best prediction I’ve seen on a Supreme Court case—see his prediction on the Ten Commandments Case.

In other news, several people have commented on my low blogging frequency of late. Unfortunately, I’ve been quite busy and thinking mostly about my work, which I can’t comment publicly on. So that leaves me with not much to say.

Filed under The Law by adam | February 2, 2005 | 0 comments

Yale Law School Professor Jack Balkin reports that two days ago, a group of Yale Law Faculty won a case against the defense department challenging the Solomon Amendment. The Solomon Amendment requires schools to provide access to military recruiters or lose federal aid—including student loans. Military recruiting is inconsistent with the campus access policy of nearly every law school in the country because of the military’s discriminatory policies with respect to sexual orientation.

The court held that the Solomon Amendment is unconstitutional as applied to Yale Law School. This is an important decision, and if upheld on appeal could signal a strengthening of the “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine, which forbids the government from restricting constitutional rights “through the backdoor” by conditioning a benefit on not engaging in otherwise constitutionally protected activity.

This was a big issue when I was in law school. I suspect the Solomon Amendment is responsible for the spam recruitment email I recently received from the Marines, although I can’t be sure where they got my law school email address (it isn’t one I’ve ever used publicly).

Filed under The Law by adam | November 9, 2004 | 6 comments

As it turns out, I passed the bar exam and will be sworn in shortly. I never received results in the mail, apparently because the court never processed my change of address. So I had to sweat it out until the results were posted on the web.

As it turns out, I passed the bar exam and will be sworn in shortly. I never received results in the mail, apparently because the court never processed my change of address. So I had to sweat it out until the results were posted on the web.

My immediate reward for passing the bar was these nice balloons. My long-term reward, I suppose, is that I never have to take that particular exam again. It’s a strong incentive to stay put for several years, so if I do move I don’t have to spend several months cramming my head with simplistic legal facts that have, at best, limited application in the real life practice of law.

Filed under The Law by adam | July 31, 2004 | 1 comment

I finished the second half of the bar exam Thursday evening. I was actually going to write a blog entry during the lunch break, perhaps to enter the book of world records as the only person ever to blog in the middle of a bar exam, but I decided it would be better to review Secured Transactions. As it turns out, there were no Secured Transactions questions on the essay portion, nor were there any Commercial Paper questions or several other areas of law I had studied intensely. It was a bit of a let-down, although I’m sure many people were happy not to see these questions.

I am firmly convinced that the material tested on the bar exam—particularly the multiple choice section—has almost no bearing on one’s ability to practice law. In fact, it might even prepare you to be a worse lawyer than you otherwise would be. Most legal questions are arguable, and if you’re in litigation it’s probably because the outcome isn’t clear. The most important skills you need to be a competent attorney involve dealing with clients, researching, writing, negotiating, developing creative arguments, etc.. Answering 200 multiple choice questions on doctrines that aren’t even the law any more in any jurisdiction (the Doctrine of Worthier Title, Shelley’s Rule, … even the Rule Against Perpetuities hardly exists anywhere unmodified) is pretty far off base.

Someday, when I have some stature in the legal community, I want to lead a charge to change this ridiculous examination once and for all. I admit that some sort of threshold exam is probably a good thing; and there might be some value to learning certain basic legal doctrine that you would not otherwise cover in law school (I certainly never learned anything about negotiable instruments).

A better exam, I think, would present you with a fact pattern that you couldn’t possibly have seen before that doesn’t fit neatly into any legal box, and ask you to analyze the situation and present possible theories for resolving the problem. Ideally, you wouldn’t even be able to classify the question as fitting into a particular doctrinal area, e.g., corporations vs. evidence. You would have to discuss how these all fit together: for example, there might be an issue of breach of fiduciary duty in a partnership but it might be difficult to ever prevail in court because of the hearsay rule and the statute of limitations.

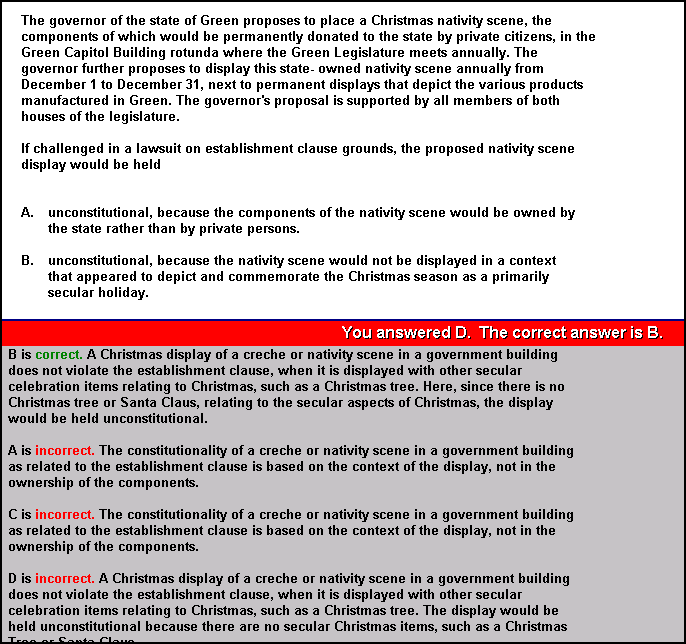

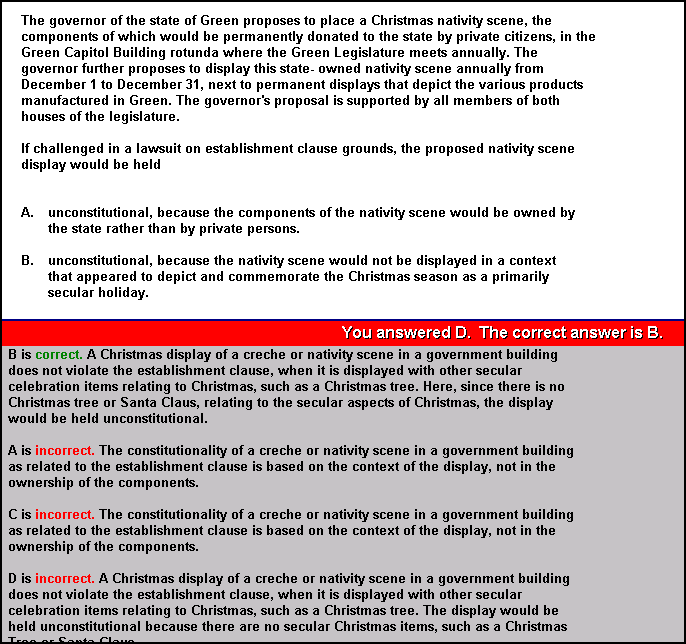

Instead, we get questions like this:

Filed under The Law by adam | July 30, 2004 | 3 comments

I finished the multiple choice part of the Massachusetts Bar Exam today. Now just ten essays, and by 6pm tomorrow I’ll be a free man, although not yet a lawyer.

One of the basic canons of the multiple choice portion of the bar exam is “if the answer is a doctrine you’ve never heard of, it’s the wrong choice.” Unfortunately, a countervailing canon is “the bar examiners often like to use less-known synonyms for well known concepts to trick you.” (I made this canon up myself, but it’s true.)

I got one of these today, and went with my intuition/countervailing canon idea, and as I’m checking it out now, it turns out I was right. The “doctrine of after-acquired title” is equivalent to “estoppel by deed.” Well, it’s actually not quite equivalent, because estoppel by deed only applies to prevent the grantor from denying the validity of a deed, invalid at the time of the conveyance because the grantor didn’t have good title at the time but did at a later date after the conveyance, while the doctrine of after-acquired title is good against other claimants, but it’s basically the same idea.

So, at least one right out of 200!

(How many hits will I get in the future on a google search for “doctrine of after-acquired title”? We shall see…)

Update: Ari points out that a google search for doctrine of after-acquired title with no quotation marks gives this blog entry as the number one result.

Filed under The Law by adam | May 13, 2004 | 0 comments

Having to pay $815 to take the Massachusetts Bar Exam is a little like having to pay Information Retrieval Charges:

“I understand this concern on behalf of the taxpayers. People want value for money. That’s why we always insist on the principal of Information Retrieval charges. It’s absolutely right and fair that those found guilty should pay for their periods of detention and the Information Retrieval procedures used in their interrogations.”

(cf. Brazil)

Filed under The Law by adam | February 24, 2004 | 0 comments

I’m just finishing studying for my penultimate law school exam ever (my last one is on Thursday), and I realized what makes a law school class great.

A great law school class doesn’t try to cram all of the doctrine from a particular area of the law down your throat. There’s no way you’re going to remember all the rules and details anyway. For many attorneys, much of their real work is legal research. As long as you know the general contours of the rules and where to look, you should be fine.

Instead, a great law school class has a small set of themes, and it attempts to show how those themes run throughout the cases you study. Those themes should be in tension with each other, and there should be instances where a given theme is, itself, self-contradictory. The class should show you how those themes developed historically, and the general “momentum” of the law at present, so you might be able to predict how a court will decide an as-yet undecided issue.

The course should push you to explore those tensions, because that’s exactly where there is an opportunity for creative lawyering.

Karl Klare·, who teaches advanced labor law, presents precisely that kind of course. I wish all law school classes could have been this good.

You might get a little bit of a sense of the course from my class notes, which I put online along with notes from almost every other law school class I’ve taken.

Filed under The Law by adam | November 20, 2003 | 0 comments

Eugene Volokh· presents a hypothetical “alcohol manufacturers lawsuit”· in which alcohol manufacturers are accused of “knowingly participat[ing] in and facilitat[ing] the secondary market where persons who are illegal purchasers . . . . obtain their alcohol.” Volokh suggests that imposing a heavy burden on manufacturers to prevent retailers from selling alcohol to people who will pass it on to minors is absurd, but that this is nearly exactly the same logic used in a recent Ninth Circuit decision involving firearm manufacturers.

My immediate reaction is that guns and alcohol are sufficiently different sorts of things that the parallelism doesn’t hold. Volokh does note that alcohol “causes” three times more deaths than guns, but I don’t think raw numbers of fatalities is the issue here. I think it’s reasonable to impose substantial duties on the entire supply chain of firearms, from the manufacturers all the way to the final purchasers. That we impose less substantial duties on the alcohol supply chain is not inconsistent: it’s a policy judgment that takes place both in the legislature and in the courts. Even if alcohol is more “dangerous” in some sense, it might be the case that: (1) we, as a society, feel that there are also more benefits associated with alcohol than with guns, and thus are more willing to tolerate the costs; (2) alcohol might just be much more costly to police (e.g., the failure of prohibition); (3) firearms affect more “innocent” third-parties than does alcohol (this might be refuted statistically); (4) perhaps the only reason there are more fatalities associated with alcohol than with firearms is because we’ve imposed substantial regulations—there’s no possible “state of nature” possible comparison between firearms and alcohol.

It’s a common rhetorical device to show how this sort of substitution gives an absurd result, but I don’t think the argument is compelling in this example. I don’t believe there is a “slippery slope” argument that attaching these sorts of duties to gun manufacturers is likely to spill over to other industries. I think it’s enough to say that commonly held social values put firearms in a different place than other items, and argument that seems silly when applied to alcohol (or, for example, pencils, which also cause a certain number of injuries) is not absurd in the context of guns.

As it turns out, I

As it turns out, I